Q & A with Petr Vidomus

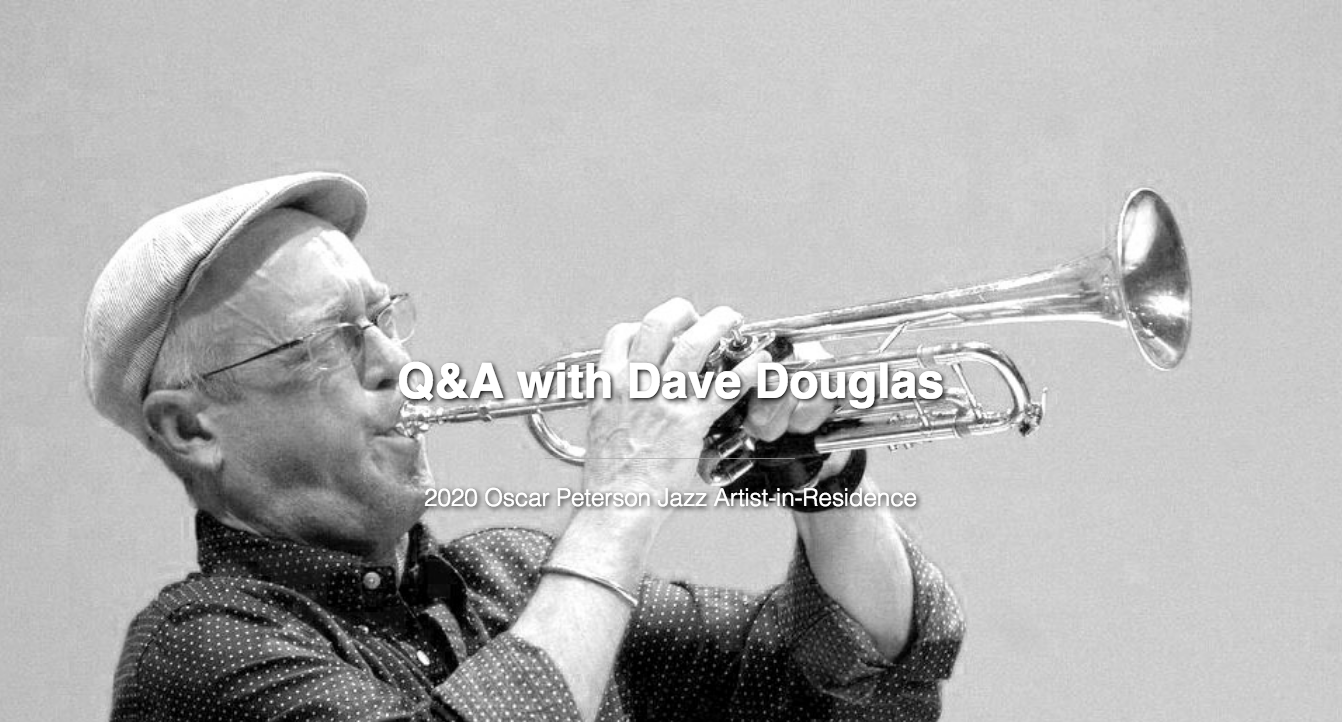

Q & A: Dave Douglas with Petr Vidomus

Harmonie Magazine, Czech Republic

January 2006

I heard that when you studied at New England Conservatory, the Carmine Caruso method was very effective for you. Can you describe what that is, why it was effective, and what suggestions you might have for trumpeters seeking to develop their own language?

It is a pleasure to be able to talk about Carmine Caruso. He saved me. I always struggled as a trumpet player – the technique did not come naturally to me. Carmine’s method enabled me to find a natural way to make sound on the instrument and then apply it to the music I wanted to play. I still study with Laurie Frink, who was the top student of Carmine’s method and now has developed her own personal approach to teaching trumpet based on her own wisdom and experience. So, in answer to your question, I urge everyone to go take a lesson with Laurie Frink! She can be reached at: LAFRINK@aol.com. I’ve spoken with her about this, and she is OK with me giving out her email. I can’t recommend her highly enough. (Full disclosure: I do not get a commission….)

Carmine taught musicians of all instruments and styles. First of all, his idea was that the technique of playing an instrument is completely separate from style or language. His feeling was that if one could learn to play the instrument in the most natural way, with the least stress and force, with a minimum amount of fuss, that one would be able to play any kind of music. I agree with that and feel that style is the mere surface of music, divorced from the basic demands of learning to play an instrument.

Carmine Caruso’s exercises begin with the premise that we are teaching the body to perform actions in time. The exercises are extremely basic, and he emphasized using a strict quarter note, subdivided, to break up each task into precisely performed actions. His idea was that by performing these exercises consciously and carefully, the body would find its own correct way of executing the notes. This helped me tremendously. After many, many teachers who told me to simply change my embouchure (where the mouthpiece is placed on the lips), Carmine got me on a path to at least being able to play consistently. I have to still practice a lot just to do that…Developing a language in music is a whole other thing. And it is equally, if not more, important. Of course there are many paths.

When asked, my suggestion is that musicians should make up their own exercises as a path to finding their own language. In other words, no matter what music you want to play, you have to study the music that has come before. And based on what you find, create your own sets of things to practice. I also think it’s valuable as you write music to create exercises and studies that use the challenges of that particular piece. That’s the way I like to work and it is how I develop new musical ideas.

You’ve worked with musicians as varied as John Zorn, Misha Mengelberg, Myra Melford, Han Bennink, Uri Caine and the What We Live Trio. Which collaborations have been more productive for you?

I learned from so many people, including all those you mentioned. I still carry with me the lessons I learned playing with Horace Silver. I also feel a debt of gratitude to musicians Tim Berne, Don Byron, Mark Dresser, Vincent Herring, Joe Lovano and others who hired me early on. Currently fulfilling for me are my collaborations with Uri Caine, James Genus, Clarence Penn and Donny McCaslin from my Quintet. With David Torn, with Jamie Saft, Gene Lake, Brad Jones, DJ Olive, Marcus Strickland and Adam Benjamin in Keystone. Over the past few years I have enjoyed playing a lot with the tuba player Marcus Rojas. I used to play on quite a few pop recordings, and I learned a lot from doing that. The collaboration with Trisha Brown was also very dear to me, as I learned so much about working with the stage, with movement, with timing, and with visual elements.

The recording engineer Joe Ferla has recorded at least a dozen of my records. You could say that’s my most productive collaboration. I love working with Joe whenever I can get him.The collaboration with Roy Campbell in creating the Festival of New Trumpet Music has been very inspiring and fulfilling for me. Roy is one of the great living masters of trumpet improvising.

Someone I admired very much though I only played with him once was Derek Bailey. His recent passing is a great loss.

I think the music on Keystone was heavily edited after recording process. The live production of the music on concerts must be really different. What´s changing?

The music on Keystone was probably not edited as much as you think. The problem of mixing live improvisation with electronics in time is one of how to maintain the flexibility and richness of both elements. Making Keystone was for me very much about finding a better way to do that. It involved a lot of pre-production work so that the actual recordings of the band could be played live in real time as much as possible. Of course there was editing after the fact also. Almost everything you hear these days has been edited to some degree. But you might be surprised to hear how much of the playing came from the original sessions.

When we play live the process is very different. My philosophy is that there’s no point handcuffing a band. I like to hear what people want to play. So we dispense with the pre-programmed, pre-created sounds, and create the pieces from the ground up. Ultimately my feeling is that if the themes I wrote are strong enough, they will hold up in these many different interpretations, while retaining their sense as compositions.

What do you think, that Roscoe Arbuckle would say to Keystone project? Haven´t you been worried that you connect things and time contexts that are just impossible to connect?

That’s a really good question! It has been fun to think about what Arbuckle might have thought about this music with his films. There’s no way of knowing, and he left no record that I could find about what he did want in terms of music. He probably didn’t feel he had so much choice, because the musical accompaniment was different in every cinema.

I would hope that after a little getting used to it he might enjoy this music and see the humor in it. Some of the music is funny, and the way it works with the film is part of the comedy. However, I also added a darker tone because I was influenced by the story of what happened to Arbuckle in a way that he could not possibly have been when he made these films.

What was the main feature (problem) in composing for the silent film? I think it was the first time you composed this way.

For me, the main problem was how to have an improvising band play with a film and not be tied into strict or static playing. What interests me in an improvising band is hearing varied amounts of freedom, and identifying every player’s personality and contribution to the music. I think that’s what makes jazz unique and powerful. My solution was to write a series of themes for the films that we could use as a basis for improvisation. The quality of themes would match scene to scene enough that the band would be able to play without having to watch the screen and match individual actions.

You have the reputation of being a voracious reader. What are the most interesting things you studied about the early times of film industry, Roscoe Arbuckle case and the social climate of the times?

I was excited to learn that many of these films were created in improvisation. They were made very quickly, and usually released immediately to theaters around the country. More people went to films then — if you can believe it, movies were more popular then than they are now.

The downside was that as each film finished its run, the copies were often destroyed to make way for new releases. We’re lucky that some of these gems even survived.

You´re going to record a new record with your Quintet soon. Could you tell us what´s the project about? What´s new compared with the previous recordings of the group?

We’re going to record a handful of new pieces that are very recent. They deal with what you might think of as the new mainstream in jazz, an idea that has shifted a lot over the past few years. Again, in writing for the quintet I write tunes — pieces that could be played by any musicians trained in jazz. This is a little different from how I write for my other groups, because though the players in the band are very important to me, I want these tunes to be able to be played by a more general body of players who are interested in going forward with the traditions of jazz.

The re-emergence of Wayne Shorter as a leader of a small improvising group has had tremendous importance for me. I feel that the way they are playing represents, in a sense, a new paradigm for how jazz tunes are performed and how improvisation works within that tradition.